Submission to Australian Senate - Grid Reliability Fund Bill 2020 by Alec Roberts18/09/2020 Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 E: [email protected] My concerns about the Grid Reliability Fund Bill 2020 Dear Senators, Thank you for the opportunity to provide a submission into the Grid Reliability Fund Bill 2020 and taking the time to consider my submission. The $1 billion Grid Reliability Fund (GRF) is a positive move to increase investment in:

However, there is no justification for expanding the CEFC’s mandate to include the funding of gas projects, especially those that are not commercially viable. The Government needs to be clear. Is the objective of this bill to firm up the electricity grid (to provide reliability going forward as additional variable renewable energy enters the grid)? Or is the objective to provide a mechanism to burn more gas? Australia will combust its carbon budget for 2050 by 2026 (See Figure 1 below) (a Senator’s term), therefore any gas infrastructure development would contribute to an unacceptable increase in greenhouse gas emissions and would be doomed to become a stranded asset. CEFC objectives are being compromised The object of the CEFC is “to facilitate increased flows of finance into the clean energy sector” through investing in businesses or projects for the development or commercialisation of clean energy technologies.[2] However, financial prudence is being abandoned, where loss making “investments” can be made by the CEFC. The proposed amendments included that CEFC would invest in technologies where individual investments under the GRF would not need to make a return. Additionally, the abandonment of building a zero-emission economy is embodied in proposed changes allowing GRF money to go to gas-powered generation (GPG), as no GRF projects need to be renewable energy projects. Therefore, if a recommended project was GPG, (which is likely given the current short list of projects in the Underwriting New Generation Investments program)[3] such an investment would prop-up an otherwise uncommercial project, forcing out more efficient and potentially lower emission technologies from the market. This would likely lead to increased prices for electricity. This is not what we want in trying to decarbonise our electricity grid without increasing prices. Low-emission technology needs to actually be net-zero-emission The fuel substitution of natural gas for coal at a glance reduces emissions for electricity generation, but that doesn’t make natural gas a low-emission technology just because you write it into legislation. This appears to be inferred by the proposed changes: “Item 33 expands the scope of “low-emission technology” to ensure the CEFC is able to invest in the GRF technologies described elsewhere in the Bill: specifically, those relating to energy storage, electricity generation, transmission or distribution or electricity grid stabilisation, and that support the achievement of low-emission energy systems in Australia. Any technology that meets this criteria will be considered a low-emission technology by default, and therefore within the CEFC’s technology remit.”[4] Natural gas as a “transition fuel”? Natural gas has often been touted as the low emission “transition fuel” for the electricity sector to replace coal’s greenhouse gas emissions and eventually paving the way for an emissions free future for Australia. The concept of gas as a transition fuel is out of date and I believe incorrect. It is simply too expensive and too emissions intensive to be so. Methane leaks from natural gas production, transportation and use can make the process nearly as carbon intensive as coal. The CEFC is already highly successful in driving investment in the most cost-effective low emissions technologies. Gas is not a low emissions technology[5] and Australia can transition to clean energy without it. The use of gas in electricity production has reduced in recent years and modelling of the future electricity grid and further evidence has indicated that it is unlikely that gas will play a major role in the transition from coal-fired power plants to renewable energy and storage. The electricity market has already moved away from gas in Eastern Australia. From 2014 to 2018, annual consumption of natural gas in NSW fell by 15 per cent, with the major contributor of this fall in consumption being the reduction in the use of gas for power generation.[6] Whereas domestic demand for gas has fallen for use in manufacturing by 14%, it has dropped by a staggering 59% for power generation by since 2014, 7 whilst renewable energy has increased by 25% during the same period.[7] Furthermore, flexible gas plants already in the grid are running well below capacity.[8] AEMO forecast that increasing renewable generation developments in the NEM are expected to continue to drive down system normal demand for GPG. [9] The AEMO modelled the future electricity grid in its Integrated Systems Plan.[10] [11] The results showed for all scenarios that the transition from coal to renewable energy would not be via gas.8 The role of gas would be reduced with a decline in gas generation through to 2040.7 The report notes that to firm up the inherently variable distributed and large-scale renewable generation, there will be needed new flexible, dispatchable resources such as: utility-scale pumped hydro and large-scale battery energy storage systems, distributed batteries participating as virtual power plants, and demand side management.10 11 It also noted that new, flexible gas generators such as gas peaking plants could play a greater role if gas prices materially reduced, with gas prices remaining low at $4 to $6 per GJ.11 However this is unlikely as gas prices have tripled over the past decade and expected NSW gas prices (for example) are over 60% more than this price.8 [12] AEMO noted that the investment case for new GPG will critically depend on future gas prices, as GPG and batteries can both serve the daily peaking role that will be needed as variable renewable energy replaces coal-fired generation. In their 2020 Gas Statement of Opportunities report, AEMO predicted that as more coal-fired generation retired in the long term, gas consumption for GPG in the National Electricity Market was forecast to grow again in the early 2030s, recovering to levels similar to those forecast for 2020.9 However, in a later report, AEMO determined that by the 2030s, when significant investment in new dispatchable capacity is needed, new batteries will be more cost-effective than GPG. 11 Furthermore, the commissioning of the Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro project in 2026 will result in less reliance on GPG as a source of firm supply.9 Moreover, AEMO forecast that, demand for GPG is predicted to continue to fall by over 85% from 2019 levels by 2028.[13] Stronger grid interconnections need less gas-powered generation AEMO noted that stronger interconnection between regions reduces the reliance on GPG, as alternative resources can be shared more effectively. 11 The expansion of network interconnections enables the growth of variable renewable energy without a significant reliance on local gas generation.[14] Supporting this assertion, the AEMO announced a series of actionable transmission projects including interconnector upgrades and expansions and network augmentations supporting recently announced renewable energy zones.[15] 11 AEMO noted that as each of these new transmission projects is commissioned, the ability for national electricity market regions to share resources (particularly geographically diverse variable renewable energy) is increased, and therefore demand for GPG is forecast to decrease.9 The Marinus Link is forecast to be commissioned in 2036, with surplus renewable generation from Tasmania then being available to the mainland National Electricity Market, which would see further declines in gas-fired generation, despite continuing coal-fired generation retirements.9 Less need for gas for ancillary services AEMO recently noted that GPG can provide the synchronous generation needed to balance variable renewable supply, and so is a potential complement to storage, with the ultimate mix depending upon the relative cost and availability of different storage technologies compared to future gas prices. 11 However, the current installation of synchronous condensers in South Australia and in the eastern states to increase system strength and stabilise the electricity network will reduce the need for gas-fired generators acting in the role of synchronous generators as more renewables enter the grid.[16] Ancillary services are likely to utilise battery storage and synchronous condensers in the future and no longer require the use of GPG. Is investment in gas wise? As an investment, gas is on shaky grounds. For example, since 2014, Santo’s write-downs are approaching $8bn. Internationally things are not better for gas. In the U.S., the number of operating drill rigs has fallen 73% in the last 12 months. And US LNG exports have more than halved so far in 2020. Deloitte estimates that almost a third of U.S. shale producers are technically insolvent at current oil prices.[17] Gas is in decline globally and further investment will lock in more unnecessary years of high emissions and will leave Australia with the economic burden of stranded gas assets. Moving away from gas The ACT is planning to go gas free by 2025. This is expected to reduce their overall emissions by 22%. As part of the ACT Climate Change Strategy 2019-2025, all government and public-school buildings will be completely powered by 100% renewable energy eliminating the need for natural gas. The ACT has also removed the mandatory requirement for new homes built in the ACT to be connected to the mains gas network and will begin to introduce new policies to replace gas appliances with electric alternatives. Some 14% of residents have already converted over to 100% electric. [18] There are moves in other jurisdictions to remove the mandatory requirement for a gas connection in new developments such as in South Australia. AEMO forecasts further reductions in gas use as consumers fuel-switch away from gas appliances towards electrical devices, in particular for space conditioning. The Commonwealth and NSW Government are exploring options to free-up gas demand through electrification, fuel switching and energy efficiency. [19] Fuel switching from gas appliances towards electrical devices can often be more economic. A 2018 study of household fuel choice found that 98% of households with new solar financially favoured replacement of gas appliances with electric. With existing/no solar 60-65% of households still favoured replacement of gas appliances with electric. [20] In the residential sector, for example, reverse-cycle air-conditioning is expected to reduce gas demand that could have arisen due to gas heating.[21] Therefore, it is unlikely that additional gas will be required in the Australian domestic gas market to meet residential, commercial, and industrial gas demand. The role of natural gas in a low-carbon economy To address the issue of dangerous climate change, Australia, along 196 other parties, is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, which entered into force on 4 November 2016. The Paris Agreement aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, by: Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.[22] The IPCC report provides an estimate for a global remaining carbon budget of 580 GtCO2 (excluding permafrost feedbacks) based on a 50% probability of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees relative to 1850 to 1900 during and beyond this century and a remaining carbon budget of 420 GtCO2 for a 67% chance (See Figure 1 for details). [23] Figure 1 Remaining Carbon Budget[24] (see below) Committed emissions from existing and proposed energy infrastructure represent more than the entire carbon budget that remains if mean warming is to be limited to 1.5 °C and perhaps two-thirds of the remaining carbon budget if mean warming is to be limited to less than 2 °C. Estimates suggest that little or no new CO2-emitting infrastructure can be commissioned, and that existing infrastructure may need to be retired early (or be retrofitted with carbon capture and storage technology) in order to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals.[25] Australia’s remaining emission budget from Jan 2017 until 2050 for a 50% chance of warming to stay below 1.5C warming relative to pre-industrial levels was estimated to be 5.5 GTCO2e.23 Adding the GHG emissions expended in 2017[26], 2018[27], and 2019[28], this leaves just 3.8 Gt CO2e remaining as at December 2019. This leaves 6-7 years left at present emission rates of the 2013-2050 emission budget to stay below 1.5°C. Therefore, at current emissions rates, Australia will have exceeded its carbon budget for 2050 by 2026. It therefore follows that no new fossil fuel development in Australia that is not carbon neutral can be permitted because its approval would be inconsistent with the remaining carbon budget and the Paris Agreement climate target. It follows that gas infrastructure development would contribute to an unacceptable increase in greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse gas and climate change – Fugitive emission Fuel switching from coal to gas has in theory the potential to reduce emissions for electricity generation. GPG in a grid with high levels of renewable energy takes the form of gas peaking plants. Gas peaking plants have only 31% less emissions than coal (not the touted 50-60%).5 Fugitive emissions from the production, transportation and use of natural gas are likely to nullify that difference in emissions from coal. The CSIRO report “Fugitive Greenhouse Gas emissions from Coal Seam Gas Production in Australia” [29] noted that fugitive emissions for Natural Gas in Australia are estimated to be 1.5% of gas extracted. It should be noted that if fugitive emissions exceeded 3.1% then the emissions intensity would match that of coal (due to the fact that methane is 86 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than CO2 over 20 years and 34 times more powerful over a 100-year time period).[30] They also noted that unconventional gas industry such as Coal Seam Gas would result in greater levels of fugitive emissions than the conventional gas industry. Furthermore, fugitive emissions from the transportation and use of natural gas appear substantive and I await with trepidation for the results of Professor Bryce Kelly’s study into fugitive emissions in Sydney.[31] Although not related to GPG, I know from my own experience that gas leaks in suburbia are quite common. Until last week (when it was finally repaired) gas would bubble up through puddles after rain on the grass verge around the corner from my house. Therefore, the use of natural gas to displace coal-fired power generation would not necessarily reduce CO2 emissions or be classed as a “low-emission energy system”. In summary, whereas the $1 billion GRF is a great move to spur on investment in:

Gas can no longer be considered a transition fuel to a low carbon economy. Natural gas is not a low emission technology and the transition to a zero-carbon grid will not be through expansion of natural gas infrastructure. Gas also appears to be in decline globally and investment in natural gas infrastructure will potentially result in stranded assets. Surely any organisation investing in the expansion of the fossil fuel industry such as the Gas industry is taking unacceptable risks with our future as well as its own. Thank you for taking the time to read my submission. Alec Roberts [1] DISER (n.d.a) Government priorities - Grid Reliability Fund. Retrieved from https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-programs/grid-reliability-fund [2] Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 (Cth) (Austl.). Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2017C00265 [3] DISER (n.d.b) Underwriting New Generation Investments program. Retrieved by https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-programs/underwriting-new-generation-investments-program [4] DISER (n.d.c) Clean Energy Finance Corporation Amendment (Grid Reliability Fund) Bill 2020. Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_LEGislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r6581 [5] ABC Radio - The Signal (2020, September 18) Why Gas? [Audio podcast]. Retrieved https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/the-signal/why-gas/12675674 [6] Pegasus Economics (2019, August) Report on the Narrabri Gas Project. Retrieved from https://8c4b987c-4d72-4044-ac79-99bcaca78791.filesusr.com/ugd/b097cb_c30b7e01a860476bbf6ef34101f4c34c.pdf [7] Robertson, B. (2020, July 23). IEEFA update: Australia sponsors a failing gas industry. Retrieved from https://ieefa.org/ieefa-update-australia-sponsors-a-failing-gas-industry/ [8] Morton, A. (2020, March 8). 'Expensive and underperforming': energy audit finds gas power running well below capacity. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/08/expensive-and-underperforming-energy-audit-finds-gas-power-running-well-below-capacity [9] AEMO (2020, March). Gas Statement of Opportunities, March 2020, For eastern and south-eastern Australia. Retrieved from https://aemo.com.au/en/energy-systems/gas/gas-forecasting-and-planning/gas-statement-of-opportunities-gsoo [10] AEMO (2019, December 12). Draft 2020 Integrated System Plan - For the National Electricity Market. Retrieved from https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/electricity/nem/planning_and_forecasting/isp/2019/draft-2020-integrated-system-plan.pdf?la=en [11] AEMO (2020b, July 30). 2020 Integrated System Plan - For the National Electricity Market. Retrieved from https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/major-publications/isp/2020/final-2020-integrated-system-plan.pdf?la=en [12] ACCC (2020, January) Gas inquiry 2017-2025 – Interim Report. Retrieved from https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Gas%20inquiry%20-%20January%202020%20interim%20report%20-%20revised.pdf [13] AEMO (2020, March 27) National Electricity & Gas Forecasting 2020 GSOO Publication. Retrieved from http://forecasting.aemo.com.au/Gas/AnnualConsumption/Total [14] AEMO (2020c, July 30) 2020 ISP Appendix 2. Cost Benefit Analysis. Retrieved from https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/major-publications/isp/2020/appendix--2.pdf?la=en [15] Energy Source & Distribution (2020, July 30). AEMO reveals Integrated System Plan 2020. Retrieved from https://esdnews.com.au/aemo-reveals-integrated-system-plan-2020/ [16] Parkinson, G. (2020, May 25) Big spinning machines arrive in South Australia to hasten demise of gas generation. Retrieved from https://reneweconomy.com.au/big-spinning-machines-arrive-in-south-australia-to-hasten-demise-of-gas-generation-64767/ [17] Robertson, B. (2020, July 23). IEEFA update: Australia sponsors a failing gas industry. Retrieved from https://ieefa.org/ieefa-update-australia-sponsors-a-failing-gas-industry/ [18] Mazengarb, M. & Parkinson, G. (2019, September 16). ACT to phase out gas as it launches next stage to zero carbon strategy. Retrieved from https://reneweconomy.com.au/act-to-phase-out-gas-as-it-launches-next-stage-to-zero-carbon-strategy-92906/ [19] Energy NSW. (2020, January 31). Memorandum of understanding, Retrieved from https://energy.nsw.gov.au/government-and-regulation/electricity-strategy/memorandum-understanding [20] Alternative Technology Association (2018, July) Household fuel choice in the National Energy Market. Retrieved from https://renew.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Household_fuel_choice_in_the_NEM_Revised_June_2018.pdf [21] AEMO (2020a, July 30). 2020 ISP Appendix 10. Sector Coupling. Retrieved from https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/major-publications/isp/2020/appendix--10.pdf?la=en [22] IPCC (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ [23] Meinshausen, M. (2019, March 19). Deriving a global 2013-2050 emission budget to stay below 1.5°C based on the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C. Retrieved from https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/421704/Deriving-a-1.5C-emissions-budget-for-Victoria.pdf [24] Figueres, C., Schellnhuber, H. J., Whiteman, G., Rockström, J., Hobley, A., & Rahmstorf, S. (2017). Three years to safeguard our climate. Nature, 546(7660), 593–595. https://doi-org.ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/10.1038/546593a [25] Tong, D., Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y., Caldeira, K., Shearer, C., Hong, C., Qin, Y., & Davis, S. J. (2019). Committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure jeopardize 1.5 °C climate target. Nature, 572(7769), 373-377. https://doi-org.ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/10.1038/s41586-019-1364-3 [26] Climate Council (2018) Australia’s Rising Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Retrieved from https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CC_MVSA0143-Briefing-Paper-Australias-Rising-Emissions_V8-FA_Low-Res_Single-Pages3.pdf [27] Cox, L. (2019, March 14). Australia's annual carbon emissions reach record high. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/14/australias-annual-carbon-emissions-reach-record-high [28] DISER (2020, May) National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: December 2019. Retrieved from https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/national-greenhouse-gas-inventory-december-2019 [29] CSIRO (2012). Fugitive Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Coal Seam Gas Production in Australia. Retrieved from https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/pub?pid=csiro:EP128173 [30] Robertson, B. (2020, January 30). IEEFA Australia: Gas is not a transition fuel, Prime Minister. Retrieved from https://ieefa.org/ieefa-australia-gas-is-not-a-transition-fuel-prime-minister/ [31] O'Malley, N. (2020, September 13). Sydney awash with leaks as research shows the climate cost of gas. Retrieved from https://amp.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/sydney-awash-with-leaks-as-research-shows-the-climate-cost-of-gas-20200828-p55qd5.html

2 Comments

Ross Brown

23/9/2020 09:58:29 am

Thanks Alec, I appreciate your work in preparing this. Good on you.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

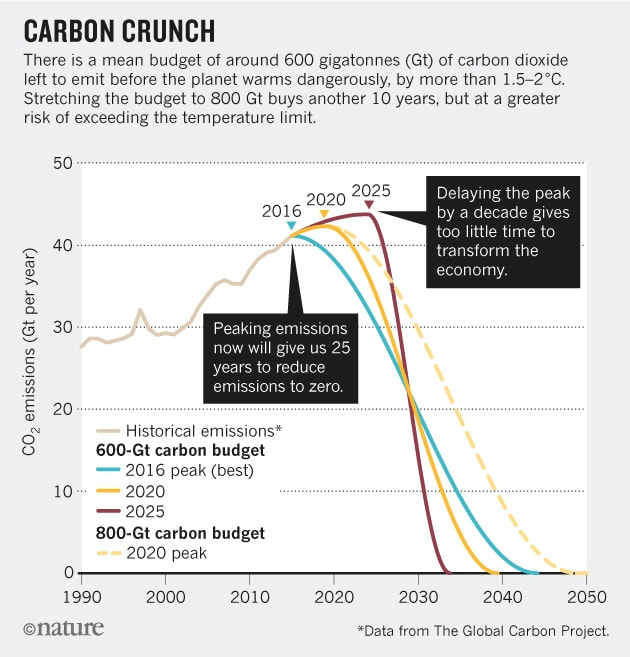

RSS Feed